The Indiana Jones of Environmental History

Shira Makin, Haaretz

The Indiana Jones of Environmental History

Shira Makin, Haaretz

March 8, 1949 was a frightening day at the Monsanto chemical plant in the town of Nitro, West Virginia. A powerful explosion was heard in one of the buildings and a black mushroom cloud erupted into the sky above it. Within minutes, black soot covered the 120 employees on site. Within hours, some of them began to report stomach pain, nausea and headaches. In the days that followed, they developed open sores on their faces, backs and legs. And that was just the beginning.

The sores didn’t heal. More and more workers were developing symptoms. Monsanto’s doctors claimed that it was merely a case of acne, offering cosmetic skin peeling as a possible treatment. This treatment only made the sores worse. Weeks passed, then months, and the workers grew accustomed to waking up in pus-soaked sheets. They suffered from depression, anxiety and sleeplessness. Anyone who spent any time in a room with them said it was impossible to ignore the strong smell of chlorine that emanated from them. The Monsanto doctors repeated the claim that what they were experiencing was simply a bad case of acne and that it would soon pass. But it didn’t. Internal documents revealed that not only the plant workers were displaying these symptoms, but also their family members, who had never set foot in the plant, as well as the doctors who treated them.

In 1953, experts commissioned by Monsanto to investigate found that the sores were caused by exposure to the chemicals manufactured at the plant, including the herbicide 2,4,5 – T. They concluded that this was not an isolated incident resulting from the blast. Their report, however, was never made public. Monsanto gave some of the affected employees cash bonuses, but demanded that they continue to work at the plant. Workers at another Monsanto plant, in New Jersey, also began developing symptoms. A doctor from Hamburg, who was investigating the herbicide in 1957, managed to isolate the component that was causing the symptoms – a carcinogenic and polluting substance called dioxin, which, years later, would come to be classified as one of the most toxic compounds in the world.

Monsanto, for its part, stepped up the production of 2,4,5-T as America embraced the weed-killing chemical. The US Forest Service adopted it, as a particularly effective tool for vegetation management on forest lands. It was used under lampposts and along train tracks. Between the years 1943 and 1952, Monsanto’s profits skyrocketed by 346%. Farmers and gardeners from all over the United States began using the herbicide, which was hailed as miraculous in the press.

It didn’t end there. More than a decade after the explosion at the Nitro plant, millions of American and Vietnamese soldiers would be exposed to a far more deadly incarnation of the dioxin-rich chemical some 14,000 kilometers from there, this time, under a different name: Agent Orange. This toxic substance was made up of two Monsanto-manufactured chemicals – 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D. The latter is still in use in agriculture today. For ten years, the U.S. military sprayed some 20 million gallons of Agent Orange on Vietnam’s vegetation in an effort to defoliate the lush jungle that was providing cover to Viet Cong cells. The chemical was transported in barrels painted with orange stripes, giving the chemical its moniker. Millions of people were exposed to the substance – both Vietnamese and American – and consequently developed skin and respiratory disorders as well as cancer. Many of their children were born with severe congenital defects. Entire forests were wiped out and never rehabilitated. Dozens of animal species were eradicated. The dioxin remains in the Vietnamese soil to this day, despite the hundreds of millions of dollars invested by the U.S. government in an effort to reverse the damage.

While this horrific story is 70 years old, it represents just one of many appalling stories that comprise Monsanto’s toxic corporate legacy. Environmental historian Bart Elmore, who received the Dan David Prize in May, recounts these in his book Seed Money: Monsanto’s Past and Our Food Future (W. W. Norton, 2021), which tells the story of the chemical company from St. Louis, Missouri that became the world’s largest manufacturer of genetically engineered seeds and changed the face of agriculture today.

“What was so shocking,” Elmore told Haaretz in a Zoom interview from his home in Columbus, Ohio, “was just how early they were seeing these systemic problems in their workers. And I think about my father, who was in Vietnam, and all the veterans and the Vietnamese citizens I met with when I went to Vietnam, who are all affected by this, even decades later, even though there was a clear record [early on] of people being exposed to a problem.”

“The most shocking thing was when those workers sued Monsanto, lost the case on what I would argue was a legal technicality, and Monsanto put liens on these people’s homes and basically said, ‘if you don’t pay Monsanto’s court costs, we’re going to take your house.’ It wasn’t shocking in the sense that I’d seen some pretty unethical behavior, but still the extent to which they were badgering these workers, who were clearly harmed by this, was one of those stops along the journey that was so hard to write about.”

“I did come into this saying, I want to be fair and show all the sides of this story, but when you’re looking at a record like that, I had to speak clearly about the unethical behavior that I thought was going on, and that was one of those moments that was really jaw dropping for me.”

Q: Do you think it’s fair to judge their actions in a contemporary context or do you give them the benefit of the doubt?

“I think one of the rules of a very good journalist or a very good historian writing about environmental history, is to be clear on when people knew what. A lot of people will say ‘it was just a different time.’ I think it’s critical to ask well, what did they know and when did they know it? With the Agent Orange story, I’m keen on pointing out that Monsanto knew there were problems with this product in 1949. 1949! It was the 1960s before the Vietnam War even happened, so they had decades to see this problem unfold. It’s not fair sometimes to say they didn’t know. That’s why the deep work of getting in there and finding the documents that show what they knew is important.”

Indeed, Elmore demonstrates in his book that the Nitro incident wasn’t an exclusive event by any means. In fact, vestiges of the toxic corporate culture that gave rise to the Nitro debacle still exist within Monsanto, which, to this day, remains one of the most infamous companies in the world. And yet, the company directly influences the agricultural crops we consume and the food that reaches our plates. Monsanto controls more than 30% of the global seed market, and its flagship herbicide Roundup is the most prevalent weed killer in the world. In the U.S. alone, Monsanto’s genetically engineered seeds are responsible for more than 85% of the corn and soy crops. “We like to think that we’re so distant from that past when in fact, it’s so recent. A document I found from 2013 reminded me that the past is not even the past, as William Faulkner said. We’re still living in it.”

The 2013 document is a confidential Monsanto presentation about a different weed killer manufactured by the company – Dicamba. In warm weather, Dicamba has a tendency to vaporize and volatilize, spreading and contaminating neighboring fields. Monsanto’s seeds were genetically engineered to be resistant to Dicamba, but when the chemical spread, it would destroy any crop that was not engineered by Monsanto to tolerate Dicamba. This meant that farmers who did not use Monsanto’s seeds would lose their crops if the chemical was used in their vicinity. In the 2013 presentation, not only does Monsanto admit to being clearly aware of this problem, it presents it as a selling strategy, explicitly saying that the best way to pitch the product was as “protection from your neighbor.”

“I don’t think I’m here to try and push an agenda, but I am here to say ‘here’s what the past can show us that we’ve done. There are lessons in this story that can help us create a more sustainable economy.’ I hope the book achieves that.”

Q: Monsanto has repeatedly promised to save the world – with drugs, with chemicals, with genetically engineered seeds – presenting these products as a way to end hunger and disease. Do you think they were ever sincere, or were they always cynical? Did they ever actually intend to do good? Did they do any good at all?

“I believe they thought that genetic engineering technology would radically reduce pesticide use, radically increase yields and that it was the best way to feed a growing population. I just believe it. Especially in the 80s and 90s, it struck me that there was a group of people that wanted to do good through their work inside Monsanto. But it’s amazing how these things go off track. Roundup is a great example – it was a billion dollar brand for the business. It was the first billion dollar herbicide in history – there was nothing like it. If you think about it in terms of the digital revolution, we might describe it as a ‘killer app’ – it was just so powerful and so effective. In certain years, farmers would have argued that this tool was really helpful and cost effective, making it easier to farm. The problem was that, like any killer app, it was used excessively and it became an obsession.”

“The vision of what genetic engineering could do in agriculture was so narrowly confined by the product pipelines that the company had. They were always thinking, ‘how can we build a trait around this brand’ instead of thinking ‘here’s a need that the farmers have, beyond herbicide use, where we can manipulate the crop and it can do amazing things.’ My book is not meant to be an indictment of genetic engineering as a technology – (holds up his phone) like anything, the iPhone can be good or bad depending on how it is used or how technologies are made and deployed. The history I offered here is really a story of how that technology was deployed in a way that was more about making profits and selling chemicals than helping farmers.”

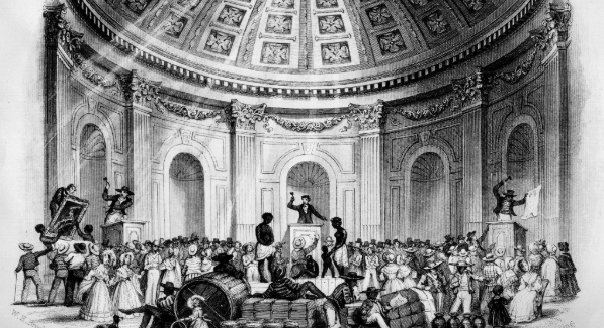

Courtesy of Coca Cola

Elmore’s interest in Monsanto came about by accident. For his Master’s thesis at the University of Virginia, he focused on Coca Cola. In the thesis, which later evolved into his first book Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism (W. W. Norton, 2015), Elmore tried to explain how Coca Cola managed to build an empire by selling a cheap concoction made mostly of sugar, water and caffeine.

“I was researching the history of the American South, the region that I was from, and I was looking to write an environmental history of a southern product that changed the world. It struck me that there was no bigger brand from the American South than Coca Cola. I think it’s the most recognized name around the world, second only to the term OK,” he says. “The idea was to write a history that looked not only at how this company expanded from a marketing and advertising angle, which so many people have written a lot about, but to think more about the natural resource story, how they got all this water and sugar and all the other ingredients to make this profitable firm. That’s how the table of contents was laid out – each ingredient was a chapter in the book and we went around the world understanding how Coca Cola got this material.”

While writing the chapter on caffeine, Elmore discovered the Monsanto link. “You can ask anyone: ‘where does the caffeine in your beverage come from?’ and most people will say ‘I have no idea, I never really thought about it.’ They would guess coffee and things like that, but most people are wrong – it ultimately came from Monsanto. That was Coca Cola’s chief caffeine supplier for many years.”

In his book, Elmore explains how Monsanto derived the caffeine it supplied to Coca Cola from broken and damaged tea leaves that the tea industry discarded as waste. “So I went to St. Louis as a graduate student, and that’s when Monsanto gave me permission to use their corporate records. That was a critical moment, because that’s when I thought, wow, I have permission to use Monsanto’s corporate records, I want to write a book about it.”

Q: The similarities between Coca Cola and Monsanto are obvious – these are two capitalist mega corporations that caused, and still cause, enormous environmental damage, harm human health and earn unimaginable amounts of money doing it. But what are the key differences between them?

“What struck me is that you have two brands that were so powerful and so global. But they were different in the sense that Coca Cola is everywhere. You walk out of your door and it’s hard not to see a Coca Cola sign somewhere. Monsanto is also everywhere – whether it’s plastic products like AstroTurf, chlorinated bisphenol – this insulating material that was used in almost everything – and of course the seeds and pesticides that provide a lot of the food around the world, it was everywhere but we didn’t see it. Monsanto was just as ubiquitous as Coke was but in a way that was more hidden. I really liked that for the second book, because everyone knew Coca Cola, but when I mentioned Monsanto to anyone outside of scholars and journalists, most people didn’t know it. I enjoyed the fact that there was a story to reveal to people, especially when they may not know that their food, and their food system, is so connected to this brand.”

Elmore, 40, is not a typical historian. His book, which spans more than 400 pages, is not a typical history book. It reads more like a true crime drama that unfolds over the course of a decade, where the villains ultimately go unpunished. Elmore weaves together the stories of farmers, workers, lawyers, powerful executives and activists alongside confidential internal memos, court documents and testimonies, into a cohesive tale of how the fossil fuel-based chemical industry became one of the cornerstones of the American economy and how Monsanto’s chemicals permeated every link in the global food supply chain. The book is full of horror stories that will make readers gasp, but it is also full of human stories, some of them touching and some of them quite amusing, like the private emails written and received by Edgar Queeny, who inherited the company from his father, the founder, and loved drinking almost as much as he loved making money.

Unlike traditional historians who are more comfortable digging through archives, Elmore went out into the world to dig up the story. He visited small southern towns where Monsanto’s factories are located; he spoke to the workers and the communities there; he showed up uninvited at Monsanto headquarters in Vietnam and Brazil; he visited the Vietnamese museum where the bloody history of Agent Orange is documented; he camped out just outside Monsanto’s radioactive sites in Idaho and even tried to infiltrate one of the company’s most toxic factories (where Roundup is manufactured) on a kayak, because the river that ran through the mine site was the only point of entry not blocked by barbed wire. Elmore is the Indiana Jones of environmental history.

“I did feel it was important for me to go to these places. If I was going to write about it, I should have some sense of what these places are like,” he explains his unconventional methodology. “I spent time at the original [Monsanto] plant in St. Louis, which is now just a graveyard in the inner corridor of St. Louis, and I just sat there one afternoon and it was just meditative to get in those spaces, to understand what it might have looked like and to be able to describe it well for a reader.”

Q: So what are you? A historian? An investigative journalist? A storyteller?

Elmore laughs. “Your profession has a real pull on me. I don’t want to say that historians don’t travel to places they write about, but I don’t think I’m being unfair by saying that a lot of historians feel a little more comfortable in archives, where most of us are trained to find our material. Anyone who leafs through the book will immediately see that I come from that archival history research – just the footnotes add up to a hundred pages. I have a lot of respect for the work of a historian. I spent nearly a decade on this material, and the pace for a historian is far slower than that of journalists. That’s mainly due to the deep archive research that I did for this book.”

“No matter what access you get to a corporate archive, if a corporation is willing to let you see it, that should tell you something. They’ve definitely gone through it, and you’re generally not going to find a smoking gun. It became clear that I needed to lean on the journalistic techniques and get out on the ground – I was clearly drawn to journalists because they had techniques and strategies that I didn’t learn as a graduate student. How do you track down a sensitive source inside a company? How do you protect that source? How do you get a smoking gun document?”

Q: Do you think, in light of Monsanto’s dreadful deeds, that historians should maintain objectivity?

“I wanted to create a tone that would invite people who might disagree with me to at least come into this book. The book is hard hitting and it tries to point out unethical decisions whenever they were made, but I also tried to show that I don’t think everyone in the firm is some kind of evil doer out to destroy the planet. I tried to tell a human story. I’m happy that the tone was achieved in a way that enabled me to have a conversation with the firm I just wrote about, which is a weird situation to be in.”

Q: Can you tell me about this conversation?

“I talked to Bayer (the German pharmaceutical company that acquired Monsanto in 2018). They reached out to me. You can actually see, the vice president of the company Matthias Berninger congratulated me on Twitter for winning the Dan David Prize.”

Q: After everything you describe in your book, like how Monsanto sent private detectives to farmers’ homes, I would personally be scared.

“Yes, I understand. It’s weird to have your subject actually reach out. In the case of Coca Cola, the response was much more antagonistic. The usual thing. It was op-eds that said that the book was not really that accurate…”

Q: And you put that on the cover of your book – that was brilliant. Two quotes appear on the cover of Citizen Coke: the first is from the Wall Street Journal and it says the book “offers a new way of looking at a major corporation. I doubt the Coca-Cola Co. will much like it” and directly below it is a quote by the Coca Cola company itself, saying “Citizen Coke demostrate[s] a complete lack of understanding about…the Coca-Cola system – past and present.”

(Laughs) “And that’s what I expected with Bayer, but the response has been very different. They said something like congratulations, this is a huge award and well deserved, and it’s very difficult to look at our dark past but we’re only going to get better if we look at our past clear eyed.”

Q: Well, their present isn’t that bright either.

“Exactly, and I think that’s it! How do we parse through this? I’ll be finding out. I’m hoping to have a little bit more conversation and we’ll see what happens next.”

Q: Why do you think it’s important to do this kind of historical research today? How is Monsanto’s past relevant to my life now?

“What this story should show is that we have a systemic problem. Not that this will be too surprising to people, but it tries to detail the systemic problems of our petrochemical-based food production system. Specifically, it tries to show why farmers are still using these techniques (using genetically engineered seeds to grow crops that are specifically designed to be resistant to the company’s herbicides) – because there’s a certain traction to this type of farming. It reduces the amount of laborers you need, the amount of weed management you have to do, it can simplify your process in some ways – all you have to do is plant the seeds, spray the seeds and viola!”

“But that ease comes at a tremendous cost, and it’s a dangerous cost. We’re facing a cul-de-sac now. Weeds are adapting and becoming resistant to all these chemical herbicides that we’re using, which makes them less and less effective, which means that we have to put more and more chemicals out into the environment. This has two consequences: It’s a cost issue and it’s a human health issue. It’s one thing to say ‘glyphosate (the active ingredient in Roundup) at low levels may not cause this or that’ – that’s a debate and people can have that debate – but when you’re talking about glyphosate on top of Dicamba on top of 2,4-D – chemicals that go back to the 1940s – that’s a deeply problematic issue. That’s what I really want people to see in the book. We’re going back in time! We’re being promised that this is the future of agriculture, but we’re using more 2,4-D than we did ten and twenty years ago – 2,4-D is a chemical that was part of Agent Orange. We’re using old chemistry, that we know is not environmentally sound, in large quantities. That’s what’s happening.”

“I hope the trajectory is very clear: We’re being promised the future of agriculture through this very high-tech looking branding with drones and digital agriculture, but the chemicals on which it is all based are from the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, before there was even an American environmental protection agency to vet all this stuff! Why this matters to all of us is because that’s a food system that is broken. I can say that definitively, having studied this for the last eight years. It is a system that is in crisis.”

Q: How does all this relate to climate change and the ecological collapse?

“Climate change is the final ace in this argument. All these products come from the waste products of the oil industry. All the things I’ve talked about require not only tremendous amounts of petrochemical feedstocks to make the system work but also an unimaginable amount of energy to produce. The plant in Soda Springs, where Monsanto mines phosphate and manufactures phosphorus, uses the same amount of electricity as the entire city of Salt Lake City! Just to melt the phosphate rock and turn it into the elemental phosphorus to make this one pesticide.”

“So if we’re serious about creating carbon-neutral agriculture, we have to get rid of this heavy chemical-input agriculture that we’ve become dependent on. I would argue that it is a product of war. It’s a product of World War II, and coming out of the 1940s, and that mindset of war. The sense that we’re at war with nature. We have to defeat nature. Instead of paying attention to nature and designing our new farming technologies to mimic life producing forces, in other words, nature. If we did that, we might be able to produce food more equitable and more justly in the future. That’s the message of the book. Don’t engage in a war on nature, do something totally different – biomimicry.”

Q: Speaking of war on nature, the U.S. and the rest of the world contaminated the soil, the well water, the air and the food just to get rid of some weeds. It’s a little extreme, isn’t it?

“The ultimate conclusion here is that farmers can effectively combat weeds, and insects too, without being so dependent on tremendous amounts of petrochemicals. It’s already happening today, a lot of farmers have reverted back to using cover crops and diversifying agricultural crops in a way that reduces the need for pesticides. I suppose that the lure of ‘clean’ weed free fields in the 1990s was one of the things that drove Monsanto’s sales. Farmers have explicitly said that they were motivated to adopt Roundup after seeing their neighbors’ fields and they wanted similar results. But it became such an obsession that it diverted the farmers’ focus away from other techniques that could have generated a more sustainable food system.”

Something is changing

When I ask Elmore whether he has changed any of his personal habits as a result of his environmental history research, he confesses that he stopped drinking Coke entirely. “I was what the industry calls a ‘heavy user’ – can you believe the term was user? I was a heavy drinker because I grew up in Atlanta, it was like water there. I loved it. It was actually a pretty big sacrifice, but I can’t remember the last time I had a Coke.” He tries to buy organic produce and avoid anything with pesticides. “This is a certain degree of privilege that I must acknowledge, to be able to buy organic food or food that doesn’t have that exposure,” he adds. But Elmore insists that avoiding products is not the solution that he is proposing. “These are such systemic things and they require us to think broadly about how we change our laws, how we change our regulations, how we source things, it’s more than Coke.”

“This is not just a consumer issue. I think that’s why I write these books – because I realize that some people see this (avoiding certain products) as a niche thing that only certain people can afford to do. But we can change that. We can change our farm policy and rules that can make this type of food more affordable. There’s no reason why a McDonald’s hamburger should be cheaper than a good salad. That’s policy and it can be changed. So hopefully, by showing how history was made, we can show how it can be unmade. I hope that this book is just one small part of that.

Q: I’m leaving this interview feeling sad. It’s hard for me to believe that we can make such a monumental difference in the short time we have left. Like Frederic Jameson said, “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.”

“I get that. But I’m also hopeful. When you get to the end of the book you’ll see that when Bayer bought Monsanto in 2018, within a matter of months, it lost half of its market capitalization as massive Roundup litigation comes forward. You’ll see states come together to file lawsuits against PCB contamination that’s still in their environment, and that’s being cleaned up for the first time ever. You’ll see that Nitro lawyer who finally won a small but meaningful victory for the people of Nitro, to get some compensation. As a writer, watching this unfold I thought ‘something is changing.’ The activism of all these people coming together and raising their voice to make a difference – call me crazy but I think it is making a difference.”

“The fact that Bayer is reaching out to me should be an indication to those folks that their work is working. This company knows that they have a problem. And in the past, they might have ignored someone like me if it weren’t for these people’s activism. It’s an indication that their work is having an effect. That people are being forced to confront the potential for change. I’ve also met enough farmers who are getting it – converting their fields to organic or converting to more regenerative agricultural practices because they think it’s more profitable and that it is the best way forward. They see it. We could be living in a moment of real change, as opposed to the past that I’ve described, and that makes me excited.”

This article originally appeared in Hebrew on April 27, 2022 in Haaretz